Understanding COVID-19 Testing

While a greater quantity of COVID-19 tests leads to higher confirmed case numbers, the World Health Organization has cited testing as ‘critical to tracking the virus, understanding epidemiology, informing case management, and to suppress transmission’. In this week’s blog post, we will help you understand the different types of COVID-19 tests, how they work, and who should consider getting tested.

What kind of testing is available?

There are two types of testing for COVID-19: viral tests and antibody tests - and both have different outcome goals. COVID-19 viral tests are conducted to determine if a patient is currently infected with the virus, while antibody tests are conducted to determine if a patient has been previously infected and is recovered.

On 07 April 2020, the World Health Organization designated two in vitro diagnostic viral tests for emergency use during this pandemic. The first is genesig Real-time PCR Coronavirus (COVID-19), and the second is cobas SARS-CoV-2 Qualitative assay, both of which are PCR-based viral tests. Since then, many companies have begun developing different viral tests, however, they must all be individually approved before becoming publicly available.

The image to the right shows an at-home kit version of the genesig Real-time PCR Coronavirus that has been approved by the FDA for purchase in the United States. Though quite expensive through personal purchase, the test allows for rapid detection of the COVID-19 strain with high efficiency.

How does a viral test work?

Step 1: A viral test begins with the collection of a sample specimen from an individual. Specimens can be collected through a few different manners depending on what the test requires. For the genesig Real-time PCR Coronavirus test, a nasopharyngeal swab, an oropharyngeal swab, or a sputum sample is required, while the cobas SARS-CoV-2 Qualitative assay requires either a nasopharyngeal swab or an oropharyngeal swab.

Nasopharyngeal swab (NPS)- a swab, similar to an extremely long Q-tip or cotton bud, is inserted into a patient’s nasal canal through the nostril. The swab is rotated to allow for nasal secretions to be absorbed, and then it is removed and placed in a collection tube.

Oropharyngeal swab - very similar to NPS, but the swab is rubbed against the tonsils and posterior pharynx through the mouth.

Sputum sample - Sputum, more widely known as phlegm, is a mucousy substance that is coughed up from the lower airways, such as the bronchi and bronchioles). Sputum is produced in larger quantities during an airway infection and the sample is collected by asking the patient to cough up and deposit the sputum into a container.

One study reports that induced sputum samples may be more accurate to diagnose COVID-19 patients than oropharyngeal swabs

The most common method of specimen collection is through a nasopharyngeal swab, as it is a quick, accurate, and safe procedure for health workers to perform on a mass number of patients.

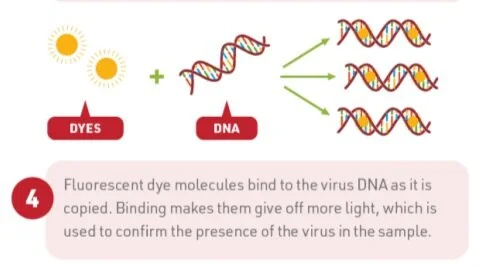

Step 2: Once the specimen is collected, it is sent to a lab to undergo real-time PCR, or real-time polymerase chain reaction. First, the sample will be treated with chemicals to isolate the RNA in the sample - this will be a mix of our own genetic material and SARS-CoV-2 material if present. Next, the RNA will be reverse transcribed (basically, copied into a DNA format), using DNA building blocks and special markers, and then will be multiplied hundreds of thousands of times so that it can be easily detected.

The key to this testing is the addition of those special markers which are marked to bind to specific genes in the viral RNA code and will work in combination with a fluorescent dye that will light-up in real-time on a screen. Depending on the location and type of test, these markers can be designed to detect different viral genes including viral proteins or specific cellular machinery. If no viral gene is present, the markers will not bind, signifying a negative result.

TL;DR, if the sample lights up the screen, it is positive for COVID-19.

Patients will be considered as testing for positive for COVID-19 if:

There is detection of at least one gene target using real-time PCR OR

If gene targets are indeterminate*, sequencing reveals the existence of the viral RdRp (a crucial part of the virus’ replicating machinery)

Lab results will return inconclusive if:

Gene targets are indeterminate AND

Not detectable by PCR or sequencing

For the general public, test results can usually be obtained within 1 week of testing.

*If a gene target is ‘indeterminate’, this means that there are either low viral quantities in the specimen or it may be a nonspecific reaction, or false signal, in the test specimen.

There are few studies that also suggest rectal and faecal sample testing can confirm the diagnosis, however, this form of testing is not widely used and is not recommended by the WHO for mass testing.

Why do we perform antibody tests?

Antibody tests can determine if a patient has had a previous COVID-19 infection, giving statistics into how many individuals have recovered from the disease. Antibody tests are not appropriate for testing if a patient currently has an infection as it can take up to 3 weeks for individuals to make high enough concentrations of the antibody to be detected in an antibody test.

Antibody tests are conducted through serologic testing, or blood tests. For COVID-19 antibody testing, blood is drawn and the plasma portion is separated. It is then subject to SARS-CoV-2 antigen which will react and bind with any SARS-CoV-2 antibodies present in the sample. (For more information on antibody formation and reaction, refer to this post). The CDC’s serologic test is reported to have a specificity of 99% and sensitivity of 96%, making it quite the reliable source for accurate testing.

Numerous companies are beginning to develop at-home kit versions of the serology test, but will need approval before public consumption.

Antibody tests are important in understanding the body’s natural immune reaction to the virus, updating recovery numbers, and finding antibody donors for convalescent plasma therapy. Monitoring who has already recovered from the virus is key, as current studies show that individuals who have been infected and recovered from the disease, are determined to be not infectious to others.

Who should get tested & can I get tested?

Governments at all levels are working to test their populations so that they can better monitor the progression and recovery of the disease. While it is ideal to test all members of the population, resources and funding may be limiting factors in global testing and therefore testing ability varies by country, province/state, and city.

Generally, individuals who experience common symptoms of the disease (such as coughing, fever, shortness of breath, or difficulty breathing) can consider being tested. Most municipalities and major cities have set up online self-assessment forms that should be taken before pursuing a viral test.

Additionally, due to high demand, individuals with mild symptoms may be recommended to stay home instead of moving to a testing location. It is best to seek out your local health department’s guidance on who should and can be tested before you make the trip.

This goes for both viral and antibody testing!

Journal Sources:

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMvcm2010260

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41575-020-0295-7

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(20)30174-2/fulltext?rss=yes&utm_campaign=update-laninf&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=84839575&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-9TBGdi1ebtVS7bApWdu-Q7ibGM6ULwekbQyL8S2tyUmgf9EoaGyt8U-87Dd7MM4fFg1zfI60R6weYX-GkXmnegD0Famw&_hsmi=84839575

Media Sources:

https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/07-04-2020-who-lists-two-covid-19-tests-for-emergency-use

https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/laboratory-services/test-information-index/wuhan-novel-coronavirus

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fabout%2Fsymptoms.html

Image Sources:

https://www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/negative-test-result-by-using-rapid-1656883729

https://www.genesig.com/products/10040-primerdesign-ltd-covid-19-genesig-real-time-pcr-assay

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMvcm2010260

https://www.compoundchem.com/2020/03/19/covid-19-testing/

https://www.webmd.com/lung/antibody-testing-covid-19

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fabout%2Fsymptoms.html